High School

Newton South High SchoolUndergraduate Education

BS in Environmental Studies from Brown University, 2022Profile

Environmental work has always been a way for Bennett Walkes to explore their relationship to identity and ancestry, but it was the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit during their sophomore year at Brown University, that created the space for this relationship to come into greater focus. Forced into lockdown and isolation, Walkes found in those first months of the pandemic a respite from the intensity that had characterized so much of their time at Brown. Having spent countless hours each week pursuing their passion for climate policy and climate organizing, they were suddenly forced to stop. There was no opportunity to protest. No organizing in support of the Green New Deal. No upcoming actions to target policymakers. With the time and space to reflect, Walkes was able to see that despite their passion for climate organizing, it had taken something from them. “It was a place where I experienced a lot of racialized harm,” Walkes notes, “including a pretty traumatic experience with a police officer at a Sunrise Movement demonstration in Washington, D.C. The pandemic was the event that separated me from all of that.”

The following summer, with lockdowns lifted, Walkes interned in a Seattle lab, testing soil samples from community gardens tended predominantly by Latine and Black communities. “The Black Farmers Collective has a farm in downtown Seattle near Chinatown,” Walkes recalls. “They would have volunteer days, so after collecting soil samples I would stay and volunteer. Sitting in circles, engaging in land-based work and community building…feeling that connection of home and place helped me understand how community-based, land-based work is a really revolutionary way of building toward the environmental future I want to live in.”

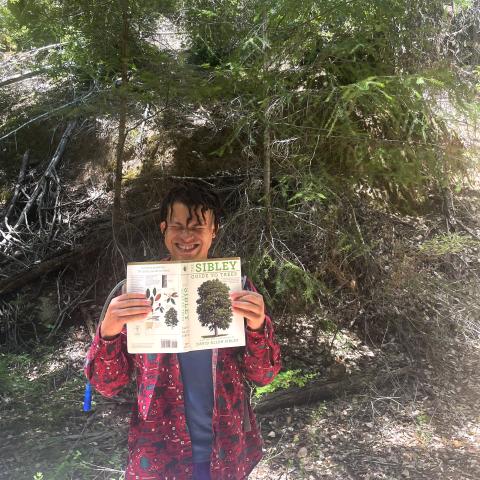

Walkes spent the next summer as a Forestry Fellow with the Shelterwood Collective, a self-described Indigenous, Black, and Queer-led community forest and collective of land protectors and cultural changemakers in California. “Indigenous and Black folks are people who have experienced real environmental harms,” Walkes notes. “Being in community with them gave me access to people seeking to repair these harms, wrestling with values of reciprocity and right relations.”

These experiences have prompted Walkes to deepen their inquiry into the relationship between justice, communities, and the land. “Black folks’ relationship to the landscape has developed over thousands of years all over the world,” Walkes points out. “A big part of white supremacy on plantations was geographic isolation, stripping people of their connection to their homeland. One of the ways that Black people resisted was by maintaining gardens on marginal land, cultivating crops from their homeland like sweet potatoes. In holding on to their culture they asserted their humanity in the face of a system that worked to strip that humanity.”

Walkes came to Brown intent on finding policy solutions to the environmental injustices that have repeatedly been inflicted on people of color, but eventually the sociological backstory to these injustices came to dominate. “When I look at the bigger systems…all of this comes back to themes of colonization, of who counts as Human, of who has agency” Walks notes. Having had these profound experiences of land-based community, a different way of living has begun to unfold for Walkes. “I want to find ways to relate to the land that are rooted in respect and reciprocity, that uplift the agency of all Humans and our more than Human kin.”